Towards the end of the 16th century, the Flemish painter Jan van der Straet, also known as Johannes Stradanus (1536–1605), designed a series of prints with the title Nova reperta, that is, “New discoveries.” Foremost among the novelties celebrated in Stradanus’ series were the nearly century-old geographical explorations of Christopher Columbus and Amerigo Vespucci that revealed a New World to European eyes. Stradanus captured the crucial moment of discovery with a striking contrast between civilized Europe as represented by Vespucci, and a savage America personified as a nearly naked woman, shaken out of her slumber by Vespucci’s arrival (fig. 1).

Ignoring the violence of Vespucci’s own meetings with the inhabitants of the South American continent, Stradanus depicted the intrepid explorer with his sword sheathed in its scabbard and his metal armor cloaked by his robes, bearing in his hands the symbols of European scientific superiority rather than military might. With his right hand, Vespucci supports a banner with an image of the stars that formed the Southern Cross – stars that Vespucci himself claimed to have described for the benefit of cosmography; in his left hand, Vespucci holds an astrolabe, the instrument with which he navigated his way across the treacherous waters of the Atlantic to the New World. Despite her obvious surprise, the figure of America does not reach for the wooden club with which Brazilians slaughtered their enemies (and then ate them; the background includes a group of natives roasting a human leg over a roaring fire). Rather, she turns towards the European with an attitude of apparent eagerness, as if to take the astrolabe from Vespucci’s hand.

Stradanus’ imagined scene of cultural encounter between European and non-European peoples implies a naive vision of scientific and technological transmission, one in which Europeans seeking political, military, economic, and spiritual dominance in the extra-European world served as passive vectors for a broad movement of knowledge from one “culture” to another. Within this conceptual framework, “European science” is an immutable artifact of European cultural superiority writ small: like the astrolabe, it remains essentially unchanged as it passes from European to non-European hands. But cross-cultural scientific circulation in the early modern era was in fact an extremely complex phenomenon.

Thanks to the plurality and longevity of European interests overseas, no easy assumptions about the intrinsic value of European science, or about the essential identity of European versus non-European culture, can explain why the seventeenth century witnessed an efflorescence of iatrochemistry in New England, Dutch-style surgery under the Tokugawa shogunate, and Tychonic astronomy in imperial China. In surveying the intellectual landscape of the Iberian and Dutch Indies, New England, New France, and the Catholic missions in Asia, this essay illustrates the malleability of Old and New World natural knowledge in extra-European locales.

The science of cosmography became a central concern for the Iberian kingdoms with the Atlantic explorations of Spanish and Portuguese navigators during the fifteenth century. Ensuring reliable navigation to the East and West Indies was a serious matter of state, while resolving territorial conflicts between Spain and Portugal depended on determining the longitude of newly discovered lands in light of various agreements, beginning with the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), which drew dividing lines from north to south to demarcate hemispheres controlled by each monarchy. If territorial disputes were somewhat defused with Philip II’s annexation of the Portuguese crown in 1580, settling and governing Spain’s overseas territories continued to pose challenges. Direction of Spain’s affairs in the Indies was in the hands of the Real y Supremo Consejo de las Indias, a body instituted by royal decree in 1524. The Council’s visitador, Juan de Ovando y Godoy (d. 1575), initiated a program to gather information about Spain’s territories in the New World by means of questionnaires to be circulated to local officials. The first royal chronicler and cosmographer (cronista-cosmógrafo) attached to the Council, Juan López de Velasco (c. 1530–1598), issued two such directives in 1577. One, a questionnaire based on earlier forms devised by Ovando, gave broad coverage to physical and historical geography. It inquired about the inhabitants, both Amerindian and Spanish; indigenous languages, beliefs, and history; buildings, regional commerce, and ecclesiastical institutions; local flora, fauna, and other natural resources; endemic diseases and indigenous remedies; local climate, rainfall, wind patterns, latitude, and regional topography; and included a request for maps of the area.

Some measure of the questionnaires’ initial success as an administrative tool can be gathered from the surviving relaciones geográficas, which comprise over two hundred sets of documents and some seventy maps, all prepared by colonial government officials in response to Velasco’s questionnaire. The officials, in turn, relied on local residents for information, from Spanish clergy to Amerindian painters. The resulting maps of Spanish-controlled territories, for instance, were a mosaic of European mapmaking conventions and indigenous traditions. The questionnaire format was notably unsuccessful, however, in eliciting cooperation from local colonial officials to queries about latitude, the altitude of the Pole Star, and date of solstice. A similar response met Velasco’s second directive, which asked recipients to record the appearance of lunar eclipses and the noonday sun, observations which would allow for systematic determinations of longitude and latitude. Although the methods which it outlined had been chosen for their simplicity, very few colonial officials seem to have carried it out, despite repeated requests in the 1570s and 1580s. Two of the four known responses came from royal cosmographers sent to the Indies in the century’s closing decades, such as the Portuguese cosmographer Francisco Domínguez, who conducted surveys, compiled geographical data, and made astronomical observations to determine latitude and longitude positions (see, Box 1).

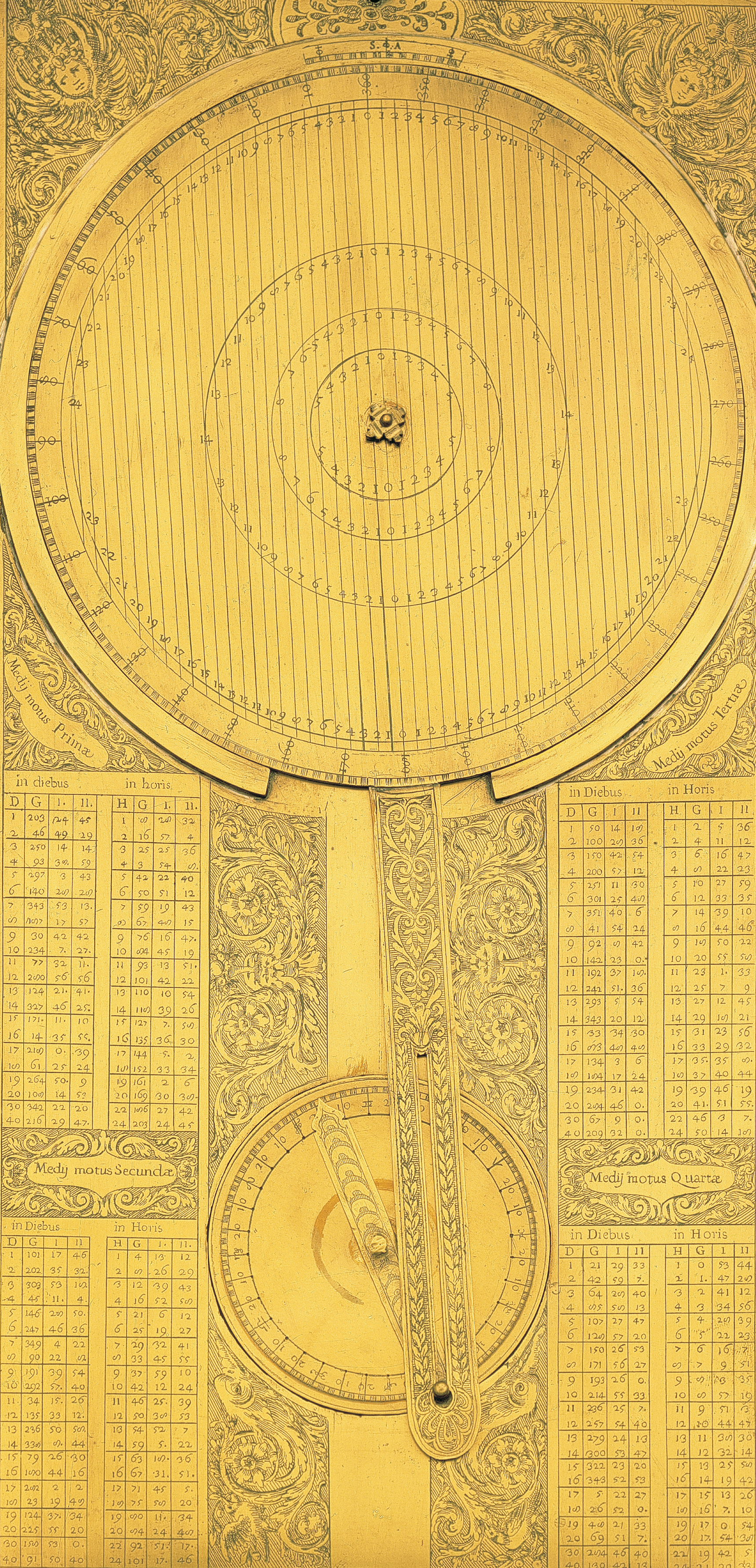

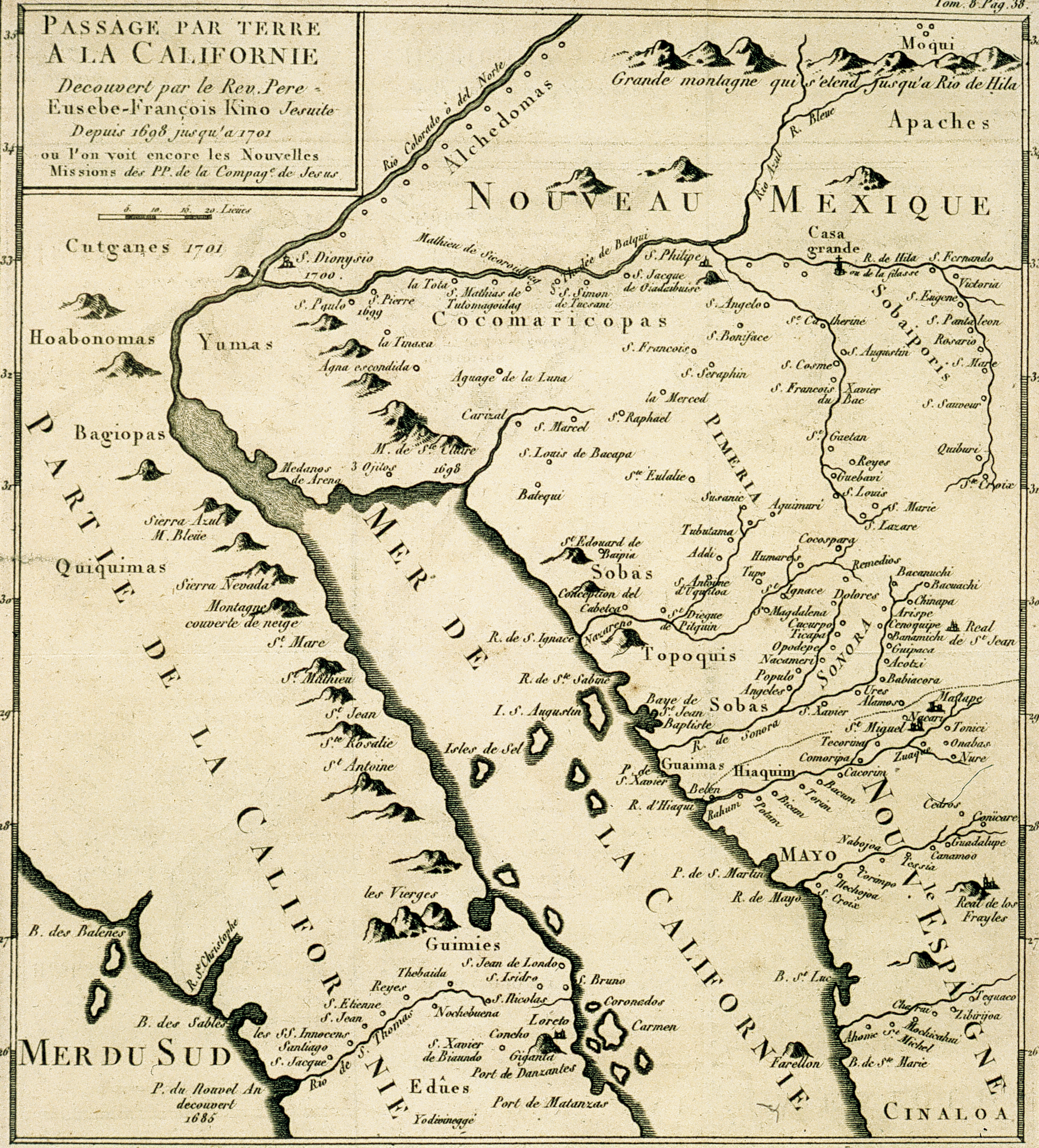

Attempts from the metropole to sustain such local data collection during the seventeenth century generated far fewer replies. In 1604, the royal cosmographer Andrés García de Céspedes sent out a questionnaire for which some thirty sets of responses are known. Another request in 1648, which sought material for the eventual use of the royal historian, apparently produced even fewer responses, while royal cédulas issued in 1679 and 1681 seem to have concentrated on demographic information. It was not until the 1740s that the Spanish government revived the questionnaire as a means of systematically compiling data on natural features of its American colonies. Instead, the burden of conducting such administrative surveys soon passed from cosmographers in Spain to their counterparts in the New World. Local officials relied on Enrico Martínez to compile reports and redraw maps made by Spanish explorers along the Pacific Coast and into present-day New Mexico. Martínez published a Repertorio de los tiempos y historia natural desta Nueva España (1606) in which he discussed the region’s climate, astrological situation, endemic diseases, agriculture, history, and geography, and also included a set of longitudes for major cities in the Iberian Indies. Professor of mathematics at the University of Mexico as well as royal cosmographer, Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora not only collated reports and charts made by others, but personally accompanied an exploratory expedition to the bay of Pensacola in 1693 to report on the area’s geography, natural resources, and native population, and to map the bay for potential Spanish settlement. Members of many an official expedition, Catholic missionaries also sometimes served as cosmographers for territories in which they hoped to open missions, as did the Carmelite friar Antonio de la Ascensión, who had studied cosmography at Salamanca. The Carmelite’s report of a 1602 journey into California included latitude positions and geographical descriptions, discussion of the flora, fauna, and the local inhabitants, and his recommendations for establishing missions and settlements. Educated in mathematics at Ingolstadt and Munich, the Jesuit Eusebio Francisco Kino sailed in 1683 as royal cosmographer with an official expedition from the Mexican mainland to Baja California. He later missionized in the northwest borderlands of New Spain, where he undertook a series of fourteen exploratory journeys. These travels resulted in substantial surveys of the region’s geography and natural history, as well as in Kino’s much-publicized map (fig. 2) which depicted California as a peninsula, not the island that Kino himself and many European cosmographers had previously supposed it to be.

Early modern Iberian expansion involved efforts to recreate Old World educational institutions wholesale, from the seminaries mandated by the Council of Trent, to colleges and schools for the humanities, and the royal and pontifical universities established at Mexico City and Lima. Where available, philosophical instruction in the Iberian Indies was largely neoscholastic in character. Yet the first holder of the chair in mathematics and astrology at the University of Mexico, the Mercedarian Diego Rodríguez, ranged far and wide in his writings on pure and mixed mathematics, drawing on authors from Nicholas Copernicus and Johannes Kepler to Galileo Galilei and Simon Stevin (1548–1620). After observing a lunar eclipse in 1638, Rodríguez consulted various astronomical tables, including those of Philip van Lansberge (1561–1632), Giovanni Antonio Magini (1555–1617), Kepler, and Christian Sørensen Longomontanus (1562–1647), to determine the longitude of Mexico City.

Scholarly work has also shown how scientific activity in 17th-century Spanish America generated its own dynamics, reflecting the complexities of a colonial society which comprised indigenous Amerindians, immigrant Europeans, and Creoles, those born in the New World of Spanish descent. In his Discurso etheorológico del nuevo cometa (1652), Diego Rodríguez offered a benign interpretation of the comet of 1652. His argument turned on the comet’s path through specific constellations – linked by Rodríguez to the Immaculate Conception – and to the Virgin Mary’s particular patronage of Mexico. Against an established literary tradition which pointed to the negative influence of the southern stars to help explain why America’s flora, fauna, and inhabitants were inferior to Europe’s, 17th-century Creole savants like Rodríguez advanced a variety of positive approaches to the New World’s celestial phenomena. This trend has been characterized in recent scholarship as a peculiarly New World brand of “patriotic astrology.”

Decades later, the comet which brightened the skies in 1680 and 1681 provoked controversy among savants not only in Europe, but in the New World as well. In an effort to debunk fearful reactions to the comet, Sigüenza penned the Manifiesto philosóphico contra los cometas despojados del imperio que tenían sobre los tímidos, but only succeeded in sparking a sharp debate among Mexican savants concerning the comet’s composition and its significance for humankind. Eusebio Francisco Kino joined the debate soon after arriving in New Spain by publishing his Exposición astronómica de el cometa (1681), in which he presented his observations of the comet which he had made at Cádiz, and discussed the comet as a portent of impending disaster. Wounded Creole pride was evident in Sigüenza’s Libra astronómica y philosóphica (1691), a caustic response to what Sigüenza perceived as condescension from the German Jesuit scholar.

Spanish universities in the New World provided advanced medical instruction, based according to statute on Aristotelian texts in natural philosophy, the Hippocratic treatises, works by Galen, and writings by the Arab physicians Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā, 980–1037) and Rhazes (al-Rāzī, 854–c.930). In 1621, a chair of surgery and anatomy was added to the two existing professorships in medicine at Mexico City, making it possible for the colonial university to grant medical degrees in accordance with newly enacted Spanish laws. Bishop Juan de Palafox y Mendoza’s 1645 statutes for the university required attendance at hospital dissections.

The three requisite chairs in medicine were created at the University of San Marcos de Lima in the course of the seventeenth century, and other educational institutions in the Spanish Americas began to offer medical teaching as well, notably in Guatemala and Quito. Regulation of medical practice in New Spain was also closely modelled after Old World patterns. Spanish law provided for the licensing of medical practitioners by a group of royally appointed examiners, the protomedicato, which had legal authority to levy fines and adjudicate matters of medical malpractice. In the early decades of Spanish settlement in the Americas, municipal authorities in Mexico City and Lima named such examiners, or protomédicos, to oversee local medical practice according to Spanish law; elsewhere, town councils took it upon themselves to at least review and validate the licence legally required of those who wished to practice medicine. In 1646, the Spanish crown tied the colonial protomedicato closely to medical teaching at the royal universities, mandating that two of the three protomedicato positions in Mexico City should be filled by university professors of medicine. Likewise, the senior professor of medicine at the University of San Marcos de Lima was to occupy the head protomédico position in the capital city of Peru (Lanning, 1985).

As in Spain, medical practitioners without university training or official license thrived despite these regulations, but the importation of such legal and institutional restrictions from the Old World suggests that medicine in the Spanish New World remained relatively conservative during the early modern period. Iberian physicians tended to view non-European medicine through the lens of their medical training, a perspective which led them to evaluate indigenous materia medica in terms of Galenic qualities and the effects of such medications in terms of humoral theory. At the same time, Iberian physicians recognized the practical and economic advantages of an inclusive pharmacopoeia. In 1570, Philip II appointed a protomédico for all the Spanish Indies, specifically instructing the Alcalá graduate and royal physician Francisco Hernández (1517–1587) to gather information from Spanish and Indian alike on New World materia medica. Hernández’s contemporaries quickly seized upon portions of his voluminous writings as a guide to practicing medicine in New Spain. An index of diseases and their corresponding indigenous remedies, based on Hernández’s work, was published in Mexico City as part of the Verdadera medicina, cirugía y astrología (1607) by the Alcalá student Juan Barrios (fl. c.1600s). The Dominican friar Francisco Ximénez published selections from Hernández’s work in his Quatro libros (1615), supplementing the volume with material drawn from his own experience working at the Hospital de Santa Cruz in the town of Huaxtepec. Ximénez intended the book to be useful in areas without doctors or pharmacies, lauding the virtues of freshly picked local plants in contrast with medicines transported over long distances.

As their missions in the Iberian Indies proliferated, Catholic religious orders established a variety of institutional contexts for studying indigenous materia medica. While the written preservation of Aztec medicinal knowledge in Náhuatl as well as European languages at the Franciscan Colegio de Santa Cruz at Tlatelolco was more the exception than the rule, Catholic religious – Franciscans, Augustinians, the Order of St. John of God – provided medical care and investigated locally available remedies throughout an extensive network of hospitals, leprosaria, and pharmacies. The pharmacy attached to the Jesuit college of San Pablo in Lima not only stocked medicines for local use, but also supplied other Jesuit houses and colleges, as well as Jesuits on their missionary travels; it even shipped Peruvian materia medica back to Europe. The passage of a Peruvian antifebrile remedy into 17th-century European pharmacopoeias dramatically demonstrated the extent and efficiency of the Society of Jesus’s medical network. Prepared from the bark of the South American cinchona tree, the drug was often referred to as “Jesuits’ bark.” Through the end of the century, the work of Jesuit apothecaries continued to reflect the immediate needs of a Catholic religious order at work in the mission fields. Paul Klein published a collection of Remedios fáciles para diferentes enfermedades (1712) in Manila, while in the same year, the lay brother Juan de Esteyneffer (Johannes Steinhöffer) dedicated his manual on diseases, surgery, and medicines, the Florilegio medicinal de todas las enfermedades (1712), to his fellow Jesuits in New Spain.

The medical profession in Portugal was regulated through a licensing regime supervised by the físico-mór and cirurgião-mór at the royal court in Lisbon; only graduates of the university at Coimbra, which possessed the sole medical faculty in Portugal and its overseas territories, could legally practice without the requisite certificate. In 1618, the Goan municipal council sought to extend this system throughout the Portuguese East Indies, decreeing that those who wished to practice medicine anywhere in Portuguese territories had to be examined and certified by the físico-mór of Goa. Far from signaling the institution of a European monopoly on medical practice, extant certificates show that Hindu practitioners were licensed under this regime during the seventeenth century, though their numbers were limited and we do not know for what sort of medical knowledge they were examined or certified. Nonetheless, in 1644 even the Goan físico-mór himself was not European. Hindu and Muslim doctors continued to practice in Goa and ministered on occasion to European patients, whether because of the often severe shortage of qualified Portuguese physicians or the patient’s preference.

Most of those who sailed from England to the New World during the seventeenth century were hardly the ideal “merchants of light” that Francis Bacon described in his New Atlantis (1627). Rather than seeking knowledge, they sought to exploit American natural resources made available through colonization. But without the sort of substantial state support that the Spanish crown provided to its overseas colonies, English colonial and mercantile enterprises experienced constant tension over how best to assure the economic survival of the fledgling settlements. The hardships of surviving in an unfamiliar land and disappointment over the lack of quick profits led many of the first English settlers in America to deride not only the English colonizing effort, but even “the countrey it selfe,” as the English mathematician Thomas Hariot (1560–1621) complained in 1588.

In order to raise support for the early English settlements on Roanoke Island, off the coast of modern-day Virginia, Hariot transformed his observations of the region and its inhabitants into A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia (1588). While his companion in Virginia drew maps of the region and sketched the local flora, fauna, and Amerindian inhabitants, Hariot paid particular attention to aspects of the natural environment that could make a colony self-sustaining, from metal ores and medicinal plants which might serve as trade goods, to foodstuffs and building supplies.

An investor himself in various English colonial and trading enterprises overseas, Bacon recognized the immediate practical value in a judicious survey of natural history, as he did in his essay Of plantations (1625). Early texts which promoted New World settlement – A map of Virginia (1612) and A description of New England (1616) by the long-time soldier and colonist John Smith, or New England’s prospect (1634), by William Wood – gave much advice about flora, fauna, climate, soil, and other features of the American landscape. Practical considerations likewise colored the observations of the colonial sojourner John Josselyn, who traveled to present-day Maine to stay with his brother, first from 1638 to 1639, and then again for most of the 1660s. Josselyn’s New-Englands rarities discovered (1672) focused on the uses to which regional flora and fauna could be put, whether as food, medicine, clothing, or other goods – a discussion which Josselyn quickly expanded in his An account of two voyages (1674), dedicated to the Royal Society of London. The naval physician William Hughes provided a similar guide for the southern English colonies in The American physitian; or a treatise of the roots, plants, trees, shrubs, fruit, herbs, etc., growing in the English plantations in America (1672).

As in the Iberian Indies, residents of the English colonies in the Americas drew substantially upon indigenous knowledge traditions to make their way in the New World. Hariot observed that the native inhabitants of Virginia used a particular kind of earth for their wounds, and enthusiastically praised the curative properties of the tobacco they smoked. Nearly a century later, Josselyn’s title page advertised his discussion of “the physical and chyrugical remedies wherewith the natives constantly use to cure their distempers, wounds and sores.” The minister John Eliot suggested in The cleare sun-shine of the gospel breaking forth upon the Indians in New England (1648) that teaching European medical knowledge to the Amerindians would persuade them to turn away from their “powwows,” shamans whose linked spiritual and healing powers posed a formidable obstacle to his evangelizing efforts. Even so, Eliot recognized native knowledge of materia medica and accepted its use, if properly divorced from what the good minister considered to be diabolical practices.

Remedies prepared from locally available vegetable and animal sources well suited the needs of most English medical practitioners in the New World, most of whom had no formal medical training. Relatively few physicians with medical degrees seem to have immigrated during the seventeenth century, and it was not until the second half of the eighteenth century that educational institutions in the English colonies began to offer medical instruction. Practitioners in the English colonies, from the midwife and ship’s surgeon to the “angelical conjunction” of the minister-physician, provided medical care free from Old World licensing and regulatory regimes.

Especially popular in New England were the vernacular herbals published during the Interregnum by the parliamentarian army physician Nicholas Culpeper, who conceived of his unauthorized translations of the College of Physicians’ official Latin pharmacopoeias as a means of disseminating medical remedies to the populace at large, in direct challenge to the College’s monopoly on medical practice. Efforts towards medical reform in Interregnum England also greatly encouraged discussion of medical chemistry, or iatrochemistry, especially as presented in Paracelsian terms by Johannes Baptista van Helmont. The libraries and pharmacopoeias of John Winthrop Jr., George Starkey (Stirk), Gershom Bulkeley, and Thomas Palmer reveal iatrochemistry’s popularity in New England with practitioners without medical degrees through the latter half of the century.

New England was especially attuned to the intellectual movements which swept through England during the Interregnum. Both the Plymouth colony, founded in 1620, and the Massachusetts Bay Colony, founded in 1630, had been refuges for English Protestants facing persecution for their dissent from the Anglican Church, a situation which worsened dramatically under the regime of Archbishop William Laud in the 1630s. The English Revolution brought the end of Anglican oppression with Laud’s fall, Charles I’s defeat and execution, and the establishment of the Commonwealth in 1649. Under the new regime, the Protestant émigré Samuel Hartlib and a group of like-minded individuals renewed their calls – often expressed in explicitly Baconian language – for agricultural, technological, and educational innovation as solutions to England’s ongoing social and economic crises. In New England, Winthrop and Robert Child promoted the establishment of ironworks and mines and sought to expand the scope of colonial agriculture, projects which paralleled the pragmatic investigations of the natural world conducted in Interregnum England. Taking advantage of a trip to England and the Continent in the early 1640s to assemble capital and expertise for his ironworks, Winthrop acquired the works of Johannes Agricola (1490–1555) as a personal gift from Hartlib, and opened a correspondence with him on chemical, medical, astronomical, and other scientific matters.

Harvard’s 1650 charter, which gave the college legal existence as a corporation, described its mission as “the education of the English & Indian Youth of this Country in knowledge: and godlines” (Morison 1936, p. 6). But despite the construction of the “Indian College,” built to house up to twenty scholars, Harvard had exceedingly few native students during the seventeenth century. Texts in Algonquian, written by John Eliot for inhabitants of the praying towns of New England and printed on the press at Harvard College, were mostly sermons, devotional works, and translations of the Bible. Even Eliot’s A logick primer (1672), written in Algonquian and based on Ramist logic, used scriptural and didactic examples. While primarily focused on educating ministers to serve the colonists of New England, Harvard College, like comparable institutions in the Iberian Americas, did not neglect natural philosophy. The plan of studies at Harvard, as detailed in New Englands first fruits (1643), included logic and physics in the first year, and mathematics and astronomy in the third, as well as “the nature of plants.”

Student notebooks manifest the popularity of Aristotelian physics through mid-century, particularly as mediated through the writings of the Cambridge graduate Alexander Richardson (c.1565–1621) and the Marburg professor Johannes Magirus (d.1596). In the 1680s, the Oxford graduate and dissenting minister Charles Morton (1627–1698) introduced more recent European thinking about the physical world into Harvard’s curriculum. Following the closure of his academy at Newington Green – an educational alternative for students unable to swear the oaths declaring allegiance to the Anglican Church and its doctrines, oaths required to attend Oxford and Cambridge – Morton emigrated in 1686 to Massachusetts, still a haven for Puritan refugees despite Charles II’s revocation of the colony’s charter and the assertion of direct royal rule.

Manuscript notebooks left by Harvard students of the period include many transcriptions of Morton’s Compendium physicae, dating from shortly after Morton’s arrival through the 1720s. Morton’s Compendium was a broad survey of natural philosophy, and probably representative of his teaching at Newington Green. While generally Aristotelian in conception, it contained much of the experimental science of the seventeenth century, from references to microscopic observations of plants, feathers, and lice, to the views of William Petty, Robert Boyle, and Henry Power on the “elasticity” of metals, the “springiness” of the air as shown in an air-pump, and the Torricellian experiment for atmospheric pressure. Morton also rejected the Aristotelian distinction between the celestial and terrestrial regions, pointing to telescopic evidence of celestial change, and sketched some of the arguments in favor of the Copernican scheme, especially Galileo’s theory of the tides and its refinement by John Wallis, Oxford professor of geometry.

Yet Morton was not the first to propound heliocentrism in England’s American colonies. Seventeenth-century almanacs published in New England – compiled for the most part by Harvard graduates and tutors, and printed exclusively on the college press in Cambridge until 1675 – included considerable discussion of astronomical topics in addition to the usual information on the positions of the Sun, Moon, and other celestial bodies. Zechariah Brigden, who took his AB degree from Harvard in 1657, cited Galileo, Kepler, Pierre Gassendi, and Vincent Wing (1619–1668) in his almanac essay for the year 1659 defending the truth of the “Philolaick” or heliocentric system. In his 1661 almanac, Samuel Cheever added Ismaël Boulliau to the list of modern authorities who had “demonstrated the Copernican Hypothesis to be most consentaneous with truth and ocular observations” (Morison 1934, p. 14), and John Foster included a woodcut of the Copernican system in his Cambridge almanac for 1675. Nathaniel Mather surveyed recent telescopic discoveries by Robert Hooke, Giovanni Domenico Cassini, and Christiaan Huygens in the Boston almanacs for 1685 and 1686, while Henry Newman noted the work of Adrien Auzout and Wallis in the discussion of the Earth’s motion that he included in the Cambridge almanac for 1690. Almanac-makers also reported unusual astronomical phenomena, including the comets which illuminated the skies in 1664 and in the early 1680s. Observations of the 1680 comet made in Boston by Thomas Brattle and perhaps John Foster appeared in the third book of the Principia (1687), in which Isaac Newton praised the work of the “observer in New England.”

New England was no exception to interest in the broader significance of comets and other extraordinary natural phenomena for humankind. One of the earliest almanac writers, Samuel Danforth, published An astronomical description of the late comet or blazing star (1665) with “a brief theological application thereof,” warning that the comet was a divine sign for New England “to awake and repent.” A minister like Danforth, Increase Mather was similarly eager to draw a moral lesson in his sermons interpreting the comets of the early 1680s as divine warnings. While the Kometographia, or a discourse concerning comets (1683) displayed Mather’s familiarity with European literature, such as Johann Hevelius’ Cometographia (1668), it was also in keeping with his providential focus on New England’s Puritan community. In 1681, Mather customized an Interregnum project to circumstances in the New World, urging his fellow ministers to work together in compiling instances of divine providence in New England. Mather published some preliminary results of this collective undertaking as An essay for the recording of illustrious providences (1684). In addition to tales of remarkable survival and accounts of demonic possession, Mather discussed wondrous features of the created world – such as observations concerning the lodestone by Thomas Browne and Robert Boyle – and recounted anecdotes concerning unusual storms, earthquakes, and floods. While Mather recited some naturalistic causes for such phenomena, he emphasized their general inadequacy. And even as he acknowledged the difficulties of accurately making such ascriptions, Mather pointed to the presence of satanic, angelic, and ultimately divine handiwork in the natural world as a guide for the Puritans in their ongoing struggle to create a godly society in New England.

A decade later, Mather tried to establish an institutional home for the collection of divine providences by addressing a proposal to other ministers in his capacity as president of Harvard College. Signed by all the College fellows, including Charles Morton, William Brattle, and Mather’s own son, Cotton Mather, the proposal named Harvard’s president and fellows as responsible for receiving and preserving contributed accounts of such occurrences.

Despite the geographical, political, and theological distance between Puritan New England and Restoration England, this collaborative effort to collect divine providences had certain affinities with the Baconian natural histories pursued by the Royal Society. Francis Bacon had advocated the compilation of a history of marvels as part of the natural history foundational to his reform of natural philosophy. Human calculi, lightning strikes, remarkable storms, and other “strange facts” were much discussed in the new scientific societies of the seventeenth century. In An essay (1684), Mather drew parallel examples of providences from contemporary European scientific literature, such as the Philosophical Transactions, Robert Hooke’s Philosophical collections, and the Miscellanea curiosa medico-physica, and he seemed to conceive of the project as closely linked to a “natural history of New-England,” recommending, in his preface, Boyle’s “rules and method” for such a work. Such emphasis on the extraordinary aspects of divine action in the everyday life of Puritan New England had little resonance in the deliberately non-sectarian scientific climate of Restoration England, and in his Compendium physicae, even Morton dismissed the notion that comets portended disaster. Cotton Mather preferred in The Christian philosopher (1721) to stress the orderliness and regularity of the natural world as evidence of divine providence, drawing on the examples of English natural theology produced by John Ray (1627–1705) and the Boyle lecturer William Derham (1657–1735). Even so, Increase Mather’s scientific predilections of the 1680s – exhibited both in the project concerning “illustrious providences,” and the unhappily short-lived “philosophical society” he organized in Boston to discuss philosophy and natural history – provided the social and intellectual context within which his son Cotton gathered materials on New England’s natural environment. The younger Mather used these materials decades later as his entrée to the Royal Society, to which he was elected a member in 1713.

Prior to 1600, French attempts to explore the Americas – from the voyages made by Jacques Cartier (1491–1557) and Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval (c.1500–1560) to Canada, to Gaspard de Coligny’s (1519–1572) sponsorship of French ventures in Brazil and Florida – were sporadic and produced no permanent settlements. The seventeenth century opened with a series of tentative efforts at combining the already lucrative trade in Canadian furs with French colonization. After spending a year at Port-Royal in Acadia, Marc Lescarbot penned the Histoire de la Nouvelle France (1609), a record of colonial experience in which Lescarbot summarized his observations on wildlife, forests, and the quality of the soil, noted the preparation of pitch from indigenous firs, and cautioned readers on the relative salubrity of the area’s prevailing winds. In 1618, the explorer Samuel de Champlain presented Louis XIII and the Chamber of Commerce with his vision for a colony sustained by a broad range of natural products unique to New France, such as timber, dye, hemp, iron, lead, and a variety of fisheries. Catholic missionaries were also acutely aware that French settlement was crucial to their hopes for the spread of Christianity. One of two Jesuit missionaries who sailed to Port-Royal in 1611, Pierre Biard transformed his varied experiences in Acadia into the Relation de la Nouvelle France (1616). Biard began his account by discussing his observations of the region’s climate, seasons, quality of soil, forests, and mineral resources, and closed by calling for the temporal and spiritual cultivation of New France (Jesuit Relations, 1616). Quebec was captured by the English in 1629. A few years after its return to French control in 1632, the Jesuit Paul Le Jeune answered a series of questions posed by potential French colonists. His discussion surveyed New France’s geography, the navigation of the St. Lawrence River, the soil’s productivity, indigenous fauna, and items valuable for trade with France, including fish, whale oil, minerals, and timber.

But systematic investigation of New France’s natural resources received little support from the Compagnie des Cent-Associés, the company established by Cardinal Richelieu in 1627 and charged with French settlement in North America in return for a monopoly on the fur trade. Nor did the Communauté des Habitants, a group comprised of Canadian settlers, take much interest in such investigations after it took over responsibility for the colony in 1645. In 1661, the governor of New France sent Pierre Boucher to seek aid from the young Louis XIV on behalf of the struggling colony, then suffering renewed attacks by the Iroquois. Boucher returned to Canada the following year, where he quickly complied with a request by Jean-Baptiste Colbert to prepare an assessment of New France’s natural resources. In his Histoire véritable et naturelle des moeurs et productions du pays de la Nouvelle France (1664), Boucher mapped out a Canadian natural history designed to promote colonization. He praised the quality of the soils and waters, explained the utility of different kinds of timber, specified the habitats of particular animals, birds, and fish, and catalogued a variety of plant life before turning to a detailed ethnography of the indigenous inhabitants. In offering suggestions as to the potential profitability of various natural products, and comments on current obstacles to exploiting the country’s riches, Boucher’s report anticipated the systematic surveys which royal representatives made throughout Louis XIV’s territories at Colbert’s urging. This administrative agenda was vital to an overall economic policy which placed heavy emphasis on industrial development, an approach soon applied in New France.

In 1663, Louis XIV reorganized the colony’s government by appointing a governor and an intendant to take over its affairs. As New France’s first intendant, Jean Talon conducted inquiries into New France’s natural resources as part of his brief to diversify agricultural production and promote a variety of manufactures, including cloth woven from the hemp and flax that Talon introduced to the colony, shoes and jackets made from Canadian leathers, beer brewed from locally grown hops and barley, and tar and potash produced from the forests of New France.

It was unfortunate that Nicolas Denys published his Description geographique et historique des costes de l’Amerique septentrionale (1672) only at the end of his active career as a merchant and colonist in Acadia, since Denys had experimented with harvesting Canadian timber, planned a flour mill and brewery, and fished the coasts south of the St. Lawrence River for over thirty years. In the first book of his Description, Denys methodically described the geography and natural history of the coast, from the Penobscot River in present-day Maine and the Bay of Fundy, to Nova Scotia and the Gulf of the St. Lawrence. In the second book, Denys provided a study of the region’s natural history which raised the utilitarian concerns of the ordinary European settler to a level worthy of royal attention. In addition to evaluating plants, animals, birds, and marine life in light of their culinary merit, Denys devoted nearly half the text to the cod fishery, which he believed could form the basis of a stable colonial economy.

The “sedentary fisheries” which Denys praised – an industry to be manned by permanent colonists in New France, rather than itinerant French fishermen – received considerable support from the new administration. The intendant also took seriously Colbert’s instructions to further investigate the possibility of a Canadian shipbuilding industry, sending expert carpenters into the forests to evaluate the timber, and encouraging colonists to learn the shipwright’s skills. Similarly, Talon organized the discovery, collection, and expert examination of mineral samples, telling Colbert but a few weeks after arriving in New France that he intended to make the discovery of such materials “an essential part of the affairs of the King and the establishment of Canada.” Though the colonial administration’s efforts to shift New France away from its dependence on the fur trade had a mixed record through the end of the century, heightened awareness of the territory’s economic potential permeated later discussions of its natural resources. During a period marked by open warfare over European colonial possessions, such emphasis had particular resonance when French authors sought patronage from other European monarchs, as did the Récollet Louis Hennepin and the soldier Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, better known as the third baron of Lahontan.

While the physician Jacques-Philippe Cornuty relied on specimens growing in Parisian gardens to write his Canadensium plantarum historia (1635), missionaries studied the natural history of 17th-century New France on the ground, drawing on their own experiences and on their extensive interactions with Amerindian peoples. In Le grand voyage du pays des Hurons (1632), the Récollet brother Gabriel Sagard included a chapter devoted to Huron medicine, and a section on the region’s flora and fauna which gave their local names and uses. The year 1632 also marked the initiation of the Relations des jésuites, an annual series published in France until 1673, which consisted of correspondence from the Society of Jesus’ Canadian missions. While first and foremost a series of letters devoted to narrating the progress of Christendom, the Relations also contained considerable material on the natural environs and indigenous peoples of New France, though Pierre Boucher commented that one would have to read all the Relations to find the information he had collected in his own Histoire véritable et naturelle de moeurs et productions du pays de la Nouvelle France (1664). Even so, the Relations provided a kind of collective natural and moral history for New France in the tradition of the Historia natural y moral de las Indias (1590) by the Jesuit José de Acosta. A little more than a year after arriving in New France, the superior of the Jesuit mission, Paul Le Jeune, wintered with a group of Montagnais. On returning to Quebec, Le Jeune described native knowledge of animals, birds, fish, fruits, and roots in the Relation for 1634. Le Jeune and later editors of the Relations often included essays on the natural history of new Jesuit missions throughout the Great Lakes, from the lands of the Iroquois, east of Lake Ontario, to Green Bay in present-day Wisconsin and the regions southeast of Hudson Bay. Similar discussions appeared in self-contained missionary narratives such as the Breve relatione (1653) by the Jesuit François-Joseph Bressani (1612–1672), and the Nouvelle relation de la Gaspesie (1691) by the Récollet Chrestien Le Clercq. French territories in the Caribbean received attention from the Dominican Jean-Baptiste du Tertre, who devoted nearly the entirety of the second book of his Histoire générale des Antilles (1667) to the region’s natural history.

The fortunes of Christendom in the New World colored missionary perspectives on its natural features. Interpretations of extraordinary phenomena as divine signs marched side by side with technical observations of their natural effects, as in the discussion by François-Joseph Le Mercier of the comets which appeared in 1664 and 1665. The Relations for 1660 and 1661 told of the earthquake, fiery apparitions, and comet which had presaged Iroquois attacks on New France. Jérôme Lalemant began the Relation for 1662–1663 by recounting the simultaneous appearance of three suns, a solar eclipse, meteors, and, most spectacularly, a series of earthquakes which shook the entire country for more than half a year. Thanks to divine providence, there was no loss of life, and Lalemant reported that these reminders of divine wrath stimulated much penitence and renewed devotion among the converts. Jesuit knowledge of the natural world also aided their missionary work. Le Jeune told the Montagnais where the Sun would rise and set on the horizon, and drew a rough map on a piece of bark to illustrate the world’s geography, hoping to thus spark their curiosity and inspire their confidence in his knowledge of still more elevated truths. Decades later, Louis André presented a sphere to an Ottawa assembly, explaining the reasons behind the changing length of days and the Sun’s path through the sky for the benefit of two local leaders who called themselves “brothers of the Sun.” The Jesuits’ ability to predict eclipses helped them shore up their credibility with the Hurons and Iroquois. As the Jesuit superior of the Canadian missions explained to the French provincial in 1683, “these sorts of eclipse predictions have always been one of the things which has most surprised our savages, and which has given them a greater idea of their missionaries” (The Jesuit Relations, LXII, p. 198).

Similarly, the Jesuits recognized early on – as John Eliot later did in New England – that European medicine could supplant the healing role held by native shamans in their communities and at the same time damage their status as spiritual leaders. Of the few books known to date from the Jesuit mission’s reopening at Quebec in 1632, several concerned medical botany, including works by Garcia d’Orta, Nicolás Monardes, and Rembert Dodoens on the exotic materia medica of the Indies. Jesuit lay brothers served as apothecaries and surgeons in New France. The first Canadian-born Jesuit, Noël Juchereau de La Ferté, was sent to study pharmacy at Lyon in preparation for the Canadian missions. The occasional donné, a layman who worked for the Jesuits in return for room and board, also provided medical care, in some cases with the help of previous medical training. Having studied surgery in France, François Gendron spent seven years as a donné with Jesuits in the Huron missions. Gendron returned to France in 1650 with an ointment made from pierres Eriennes – stones which he found by Lake Erie – and became a renowned doctor; in 1664 he was called to treat the queen mother, Anne of Austria. René Goupil was also a surgeon before becoming a donné, though his career turned out rather differently. A few days after taking vows as a Jesuit brother, Goupil was killed by the Iroquois.

Jesuits made no objection to the use of indigenous “natural” medicines, which included bleeding and a variety of herbal remedies, so long as such methods were not accompanied by what they considered to be superstitious rituals. But by supplying their own efficacious “natural” cures – bleeding, sugar, dried fruits, compounded drugs – and by substituting their own “supernatural” remedies of prayer, relics, and holy water, Jesuits hoped to gain repute and good favor with the natives as a prelude to preaching the truths of Christianity. With such notions in mind, Le Jeune urged the founding of a hospital in New France in the Relation for 1635, and the following year reported that Madame de Combalet – later made the Duchesse d’Aiguillon by her uncle, Cardinal Richelieu – intended to take on this enterprise. In 1639, three Hospitalières nuns arrived at Quebec to staff the Hôtel-Dieu, the first of several hospitals established in New France during the seventeenth century. With no medical degree-granting institution and very few immigrant physicians with formal qualifications, New France depended on a wide variety of medical practitioners – missionaries, hospital nuns, army and ships’ surgeons, and midwives – to care for the health of its settler and indigenous population.

In Les voyages (1613), Champlain provided the reader with numerous charts for Canadian ports of call and a spectacular “Carte géographique de la Nouvelle France.” Based on his own travels and information gathered from native informants, the map detailed the Acadian coastline and the network of tributaries leading to the St. Lawrence River as far inland as Lake Erie. While making good use of the stars and Sun to determine latitude, Champlain was convinced by Guillaume de Nautonier’s Mecometrie de Leymant (1603) that lines of constant magnetic declination could serve as a means for determining longitude. He instructed his readers that the larger “Carte géographique” was designed for those who chose to navigate to the New World without correcting their compasses, which, in France, varied towards the northeast. Champlain included a second map of New France constructed “on its true meridian,” that is, with the “north” of the map set towards the northwest; he based this orientation on his own observations of magnetic declination. Champlain retained his interest in navigation to the end of his long career. A veteran of some twenty voyages to New France, Champlain published his Traitté de la marine et du devoir d’un bon marinier (1632), in which he recommended knowledge of a variety of navigational instruments and techniques, and ended with prescient advice about the importance of finding and encouraging good navigators.

Thirty years after Champlain, navigation of the St. Lawrence River was still extremely hazardous, according to Jean Talon, despite the work of the surveyor Jean Bourdon, who had mapped the river as far inland as Montreal. A donné in the Jesuits’ service, Martin Boutet de Saint-Martin began teaching mathematics during the early 1660s at the Jesuit college in Quebec. Talon wrote to Jean-Baptiste Colbert in 1671 of the colony’s need for trained pilots, reporting that he had encouraged the Sieur de Saint-Martin to undertake such instruction, and advising that the crown ought to provide him some compensation. These actions reflected the mandate throughout Colbert’s administration to improve hydrographical instruction in France, a fundamental element in the minister’s broader program to reform the French navy. Part of the science of hydrography, navigational problems were often treated in the seventeenth century as a branch of mixed mathematics, as they were in the Hydrographie (1643) by the Jesuit professor of mathematics at La Flèche, Georges Fournier. As such, hydrography increasingly became part of the French educator’s brief in the latter half of the seventeenth century, notably in Jesuit institutions which expanded existing mathematical instruction – part of the standard philosophy course – to accommodate Crown priorities. The Jesuit college of Quebec was an instance of this broader trend.

Boutet’s influence on Canadian pilots seems to have been substantial. The new governor of New France, Brisay de Denonville, reported soon after taking up his post in 1685 that Boutet’s death was keenly felt. Writing to the Marquis de Seignelay, Colbert’s son and his successor as minister of the navy, Denonville proposed Jean-Baptiste Louis Franquelin and the explorer Louis Jolliet as suitable replacements. Already known for his cartographical work on behalf of the colonial government, Franquelin was named royal hydrographer in 1686 and provided with a yearly stipend.

Official establishment of the position signaled the importance of hydrography for a colony whose survival depended so heavily on its waterways. Franquelin proved to be more attentive to his cartographical projects than to his educational responsibilities at Quebec, and returned to France in 1692, where he continued to make maps of the New World. Jolliet replaced him in 1697, his qualifications based on his extensive journeys throughout New France, most notably his exploration of the Mississippi with the Jesuit Jacques Marquette, a visit to Hudson Bay, and his reconnaissance of the Labrador coast. In the meantime, the Jesuits had begun teaching a course at Montreal; some who had studied there with Claude Chauchetière were already at sea in the early 1690s. The Jesuits also took over hydrographical instruction at Quebec during Franquelin’s absence, and again after Jolliet’s death.

Making good use of the mixed mathematics that was part of their formation, Jesuits in New France had long paid attention to lunar eclipses, solar altitudes, and magnetic variation in order to map their increasingly far-flung mission stations. Navigating the complex inland waterways which made up the Great Lakes system similarly invited Jesuit observation of winds, tides, and currents, whether in the waters linking Lake Huron with Lake Michigan, or in Green Bay in present-day Wisconsin. With the exception of Jean Deshayes – to whom the Jesuits lent mathematical instruments and books – 18th-century royal hydrographers in New France were all members of the Society of Jesus and professors at the Society’s college in Quebec.

Founded in 1621, the Dutch West India Company (WIC) soon seized Brazil from the Portuguese and named Count Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen as its governor-general for the region, which it controlled until 1654. During his seven-year tenure (1637–1644), Maurits created a princely court in Brazil, assembling an exotic garden, a collection of rare birds and animals, and a group of European scholars and artists to document Brazil’s natural riches. The latter ensemble included Georg Markgraf, a student of botany and astronomy at numerous central European universities, notably those of Rostock, Stettin, and finally Leiden. Having obtained passage to Brazil with the WIC, Markgraf caught the governor’s attention with his engineering skills. Maurits provided Markgraf with a guard of soldiers to accompany him on his botanizing journeys in Brazil, and with space in one of his own residences for an astronomical observatory. Willem Piso (Pies) had studied medicine at Caen before going to Brazil as Maurits’ personal physician and chief doctor for the Dutch troops. Though Maurits was soon recalled by the Dutch West India Company, he was determined to leave a lasting legacy of his tenure in Brazil, and after returning to Holland he supported the publication of Piso and Markgraf’s materials.

Markgraf had intended to compose an ambitious work of astronomy and cosmography, which was to comprise his observations of the southern skies, made with instruments of Tychonian design; new theories for Venus and Mercury; work on refraction, parallax, and sunspots; geographical material; and astronomical tables. After Markgraf’s premature death, his former professor in astronomy at Leiden, Jacob Golius, took over responsibility for these manuscripts, but most were never published. Despite being written in cipher, Markgraf’s notes on Brazilian flora, fauna, and the local inhabitants, together with his meteorological and geographical observations, were eventually edited and published as part of the Historia naturalis Brasiliae (1648) by one of the directors of the WIC, Johannes de Laet. A volume which also included Piso’s texts on Brazil’s “air, water and places,” diseases, poisons, and materia medica, de Laet’s edition was a major publication in folio, and featured several hundred woodcuts, based largely on work by Dutch artists in Maurits’ service.

The “Christian century” in Japan began with the arrival in 1549 of the Jesuit Francis Xavier. Reflecting on his experiences, Xavier noted the curiosity which the Japanese expressed towards Jesuit knowledge of the natural world, such as the sphericity of the Earth or the causes of hail, and Xavier remarked that discussion of such topics gave the Jesuits the desirable reputation of being learned men. He recommended to the Society of Jesus’ founder, Ignatius of Loyola, that Jesuits sent to Japan should be versed in “the celestial sphere” and other natural phenomena. General cosmological concepts were enlisted on behalf of Christian apologetics, as when the Japanese Jesuit Fabian Fucan scored points against the Buddhist belief in the western paradise by pointing out in his Myotei mondo (Myotei dialogue) of 1605 that the Earth was not flat. Such arguments were not always convincing. Debating with Fabian the following year, the scholar Hayashi Razan repeatedly criticized the Jesuit claim that the Earth was round, objecting specifically to the Aristotelian notion that Earth’s natural motion was towards the center of the universe.

In the early decades of the seventeenth century, the Tokugawa shogunate sought to insulate Japan from the Portuguese and the Christian religion, relying on forced recantations, executions of Christian converts and missionaries, and a ban on importing Chinese books which dealt with Christian teachings. Imposed in 1630, the ban specifically prohibited the Tianxue chuhan (1626) and other texts recently authored by Jesuit missionaries working in China, several of which dealt with geography, hydraulics, astronomy, and mathematics. Even so, a tradition of Nanban-gaku – a “Southern Barbarian learning” identified with the Portuguese – did survive in 17th-century Japan. Originally written by the Jesuit Pedro Gomez (1535–1600) for teaching purposes in Japan, a late 16th-century manuscript became the basis of an astronomical treatise by Kobayashi Yoshinobu, which included discussion of epicyclic models, celestial spheres, and telescopic observation. Confined for some twenty years as a suspected Christian, Kobayashi went on to teach astronomy in Nagasaki upon his release in 1667.

The Jesuit Christovão Ferreira apostatized under torture in 1633 after more than two decades of missionary work in Japan. Formerly the vice-provincial for the Japan mission, Ferreira converted to Buddhism and took the name Sawano Chuan. Possibly translating a text brought to Japan in 1643 by a group of Jesuits – all of whom were forced to apostatize with Ferreira’s assistance – Ferreira composed an Aristotelian picture of the universe, from the four elements and the four qualities to the sphericity, immobility, and centrality of the Earth, and a variety of terrestrial phenomena. He then gave a detailed discussion of Ptolemaic spherical astronomy, covering such topics as the number, order and motion of the celestial spheres, the inequality of days, eclipses, and the dimensions of the universe. With the help of a translator, the Confucian scholar Mukai Gensho transcribed Ferreira’s romanized text into Japanese script and added a preface and critique, all of which was collectively titled Kenkon bensetsu (Heaven and Earth with commentaries, c.1650), and circulated in various manuscript versions. A number of other printed and manuscript texts referred to cosmological ideas derived from Chinese-language books by Jesuit authors. Yet Mukai Gensho’s son, Mukai Gensei, was the inspector of books who broadened enforcement of the import ban in the closing decades of the century, and the prohibition was not relaxed until 1720.

Contact with the Portuguese gave rise to a tradition of Nanban-ryugeka, or “Southern Barbarian-style surgery,” and one surviving manuscript with such a title was attributed to Ferreira. It has been suggested, however, that Ferreira obtained his knowledge of medicine through observing Dutch doctors at work, and when the text was eventually published towards the end of the century, its title reidentified the contents – humoral theory, the treatment of wounds, materia medica – as Oranda-ryu geka, or “Dutch-style surgery.” During the tumultuous imposition of the sakoku, or “closed-country” policy by the shogunate, representatives of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) successfully distanced themselves from the Portuguese and Spanish, who were effectively banished from Japan by 1640. The Dutch East India Company’s subsequent monopoly on direct European trade meant that its personnel monopolized the exchange of scientific knowledge between Japan and the West, largely superseding the Jesuit missionaries as mediators of cultural exchange. Though almost exclusively confined to the island of Deshima in Nagasaki’s harbor, continued Dutch presence in Japan fostered growing interest in the practices of Company surgeons and doctors stationed at the VOC factory.

The Company doctor Caspar Schamberger attracted great interest when he accompanied two Dutch embassies to the shogun’s court at Edo around mid-century, and from his teaching emerged a tradition of Caspar-ryu geka (Caspar-style surgery). Schamberger’s successors even signed certificates attesting to the competency in Dutch surgery and medicine of Japanese practitioners, many of whom came from the ranks of Dutch interpreters. Japanese physicians professing knowledge of Dutch medicine attained positions as Bakufu (shogunate) physicians in the century’s closing decades, and various lineages of Komo geka (Red-hair surgery) were propagated well into the eighteenth century.

We have already seen considerable evidence that early modern European missionaries scrutinized the nature of the new worlds that they sought to Christianize. More evidence lies hidden in the voluminous correspondence of the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680), professor of mathematics in the Society of Jesus’s Collegio Romano. Still held in the archives of the Pontificia Università Gregoriana and presently the subject of an internet edition by the Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza in Florence, the fourteen folio volumes of manuscript material provide a cross-section of the early modern Republic of Letters and a glimpse into the scientific activities of Jesuit missionaries during the seventeenth century. Some of this accumulated material made its way into publication. In the Magnes sive de arte magnetica (1641) and its later editions, Kircher tabulated observations of magnetic variation and dip in an effort to correlate such readings with longitudinal and latitudinal positions. Culled from Kircher’s own correspondence and from the archives of the Collegio Romano, many of the contributions came from fellow Jesuits traveling to and from their missions in the Indies. Kircher himself had asked to go to China as a missionary. His requests denied, Kircher gave textual expression to his combined interests in the overseas missions and the wonders of art and nature by publishing the China illustrata (1667). His fellow Jesuits contributed much to the volume. In his discussion of Chinese natural history, Kircher cited works already published by Jesuits in the Asian missions: the Novus atlas sinensis (1655) by Martino Martini, who had sent Kircher astronomical and magnetic observations from Goa and Macau, and the Flora sinensis (1656) by Michel Boym. Kircher also drew on considerable manuscript material, and alluded to a Plinius Indicus by Johann Schreck (Johannes Terrentius), who had been a member of the Accademia dei Lincei founded by Federico Cesi (1585–1630). Schreck prepared annotations and commentary for the Lincei edition of Francisco Hernández’s work on Mexican natural history, and seems to have written a comparable work dealing with the East Indies; the manuscript of this Plinius Indicus has yet to be located.

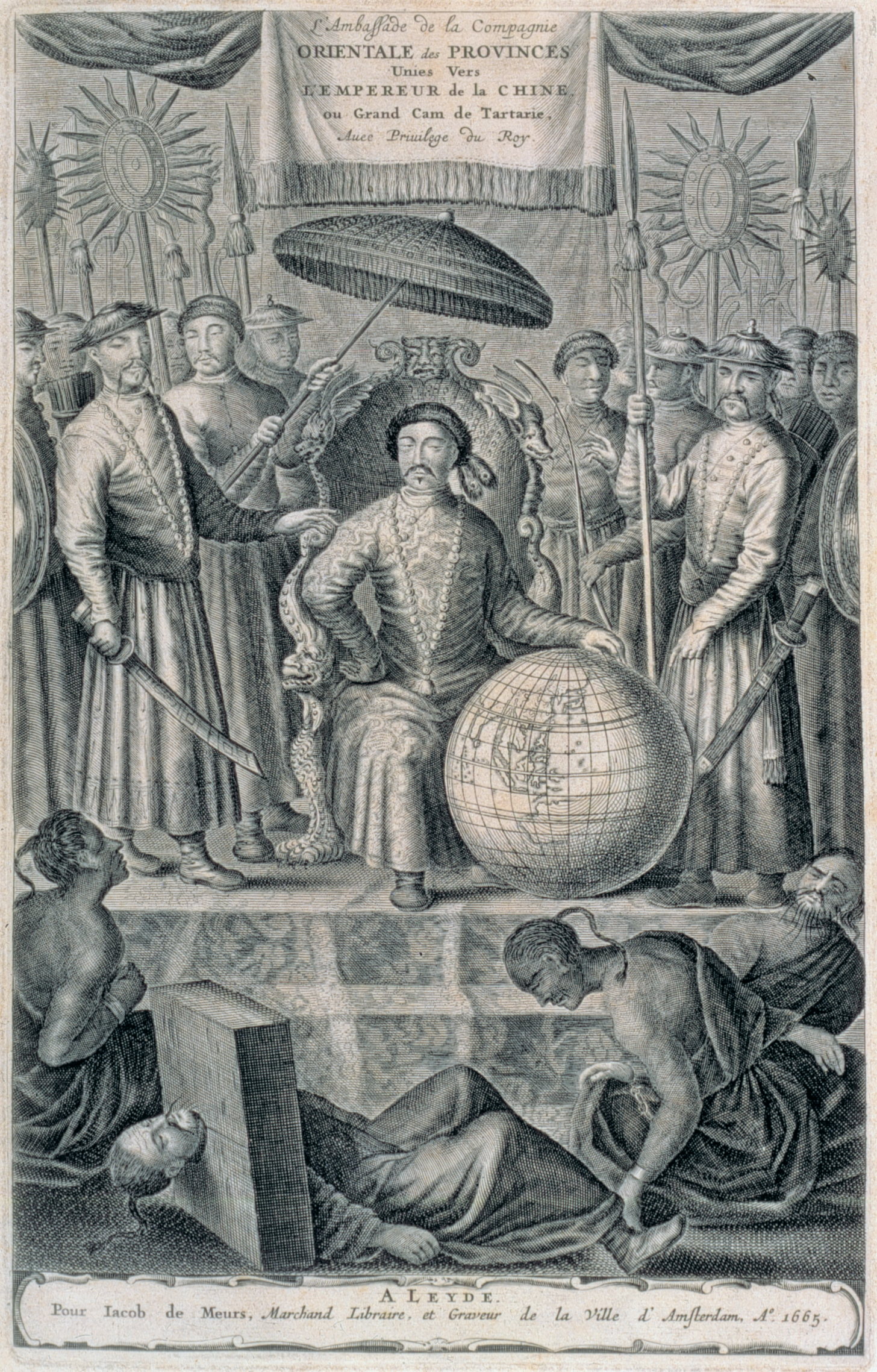

Jesuit scientific activity in China was not limited, however, to European audiences. In his China illustrata (1667), Kircher framed his narrative of the Jesuit mission in China with Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), whose knowledge of the natural sciences served to elicit the interest of the Chinese elite, and Johann Adam Schall von Bell, who ascended to the highest ranks of Chinese officialdom as imperial astronomer. The trajectory of Jesuit science in China was rather more complex than Kircher’s discussion suggested. Even so, his volume indicates the extent to which Jesuit missionaries had integrated European science into their efforts to expand the eastern boundaries of Christendom.

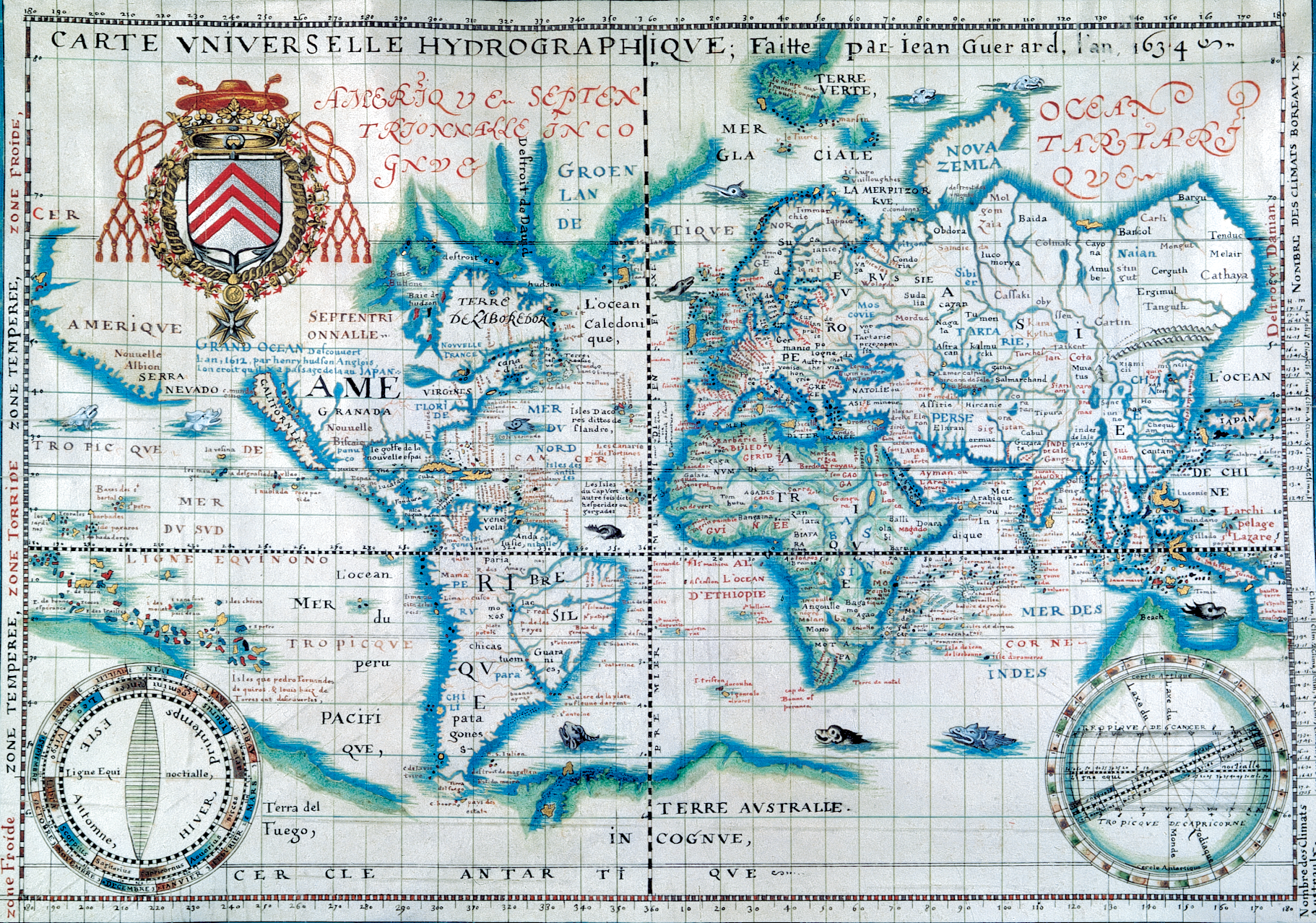

Despite his studies at the Collegio Romano with the renowned Christopher Clavius, Matteo Ricci only gradually came to realize how his knowledge of astronomy and mathematics might serve the Jesuit mission in China. But Ricci and his fellow Jesuits eventually discarded the Buddhist garb and appearance they had initially adopted in China in favor of the long beards, silken robes, and social advantages of the Chinese literati. They likewise learned to capitalize on the attraction that clocks, maps, and astronomical instruments had for the Chinese learned élite. Chinese scholars were eager to learn more about the author of a map that so strikingly depicted the world beyond the Middle Kingdom. The 1602 Beijing edition of Ricci’s world map was extensively annotated with place-names, geographical descriptions, and essays on various topics in European natural philosophy, including the sphericity of the Earth, the five climatic zones, the system of longitude and latitude, a discussion of eclipses, and a geocentric cosmology complete with nine celestial spheres.

To flesh out this skeletal description of the natural world, Ricci and his fellow missionaries turned especially to Jesuit texts representative of contemporary European natural philosophy at the beginning of the seventeenth century. John of Sacrobosco’s brief 13th-century text concerning the celestial sphere was the basis for an extensive commentary by Christopher Clavius. Available in several editions through the early 1600s, Clavius’ text served the early Jesuits in China as a source for Aristotelian cosmological notions. Ricci collaborated with the scholar and Christian convert Xu Guangqi to translate the first six books of Clavius’ textbook on Euclidean geometry, and worked with Xu and another prominent convert, Li Zhizao, to turn other writings by Clavius on mathematics and astronomical instruments into polished Chinese.

In the last decades of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Ricci’s successors wrote on a broad range of topics in Aristotelian natural philosophy, often making use of the “Conimbricenses,” the Aristotelian commentaries based on instruction at the Jesuit college of arts in Coimbra and published in numerous editions between 1592 and 1631 in Portugal, France, Venice, and the Holy Roman Empire. Niccolò Longobardo, Alfonso Vagnone, and Francisco Furtado drew on the Meteorologica and De caelo et mundo to author texts on a variety of terrestrial phenomena. Giulio Aleni and Francesco Sambiasi relied on De anima and the Parva naturalia to expand on Aristotelian concepts of human psychology and the principles of all living things, inanimate and animate. Both Aleni and Johann Adam Schall von Bell presented Galenic theories of human physiology to Chinese readers, while Aleni also wrote geographical works which painted glowing portraits of Europe’s educational system and traditions of learning. Johann Schreck and Giacomo Rho contributed discussions of human anatomy; Rho drew in particular on the work of Ambroise Paré (c.1510–1590).

Jesuits also sought to attract official attention to European scientific expertise. In 1612, Xu Guangqi and Sabatino de Ursis collaborated on a work concerning water technology (Taixi shuifa) – a text relevant to issues of agriculture and water control which Xu had long studied as a matter of statecraft. In the mid-1620s, another Christian convert, Wang Zheng, worked with Johann Schreck to compile a text on mechanics and mechanical devices, to which Wang added his own essay on agricultural machines.

A decade later, Li Tianjing repeatedly wrote to the imperial court about the ways in which Western mining knowledge and metallurgy, available in Schall’s translation from De re metallica by Georg Agricola, would be useful in the war against the Manchus. Schall presented this text and a work on firearms to the throne in 1643. In the last months of the Ming dynasty, the Chongzhen emperor ordered that Schall’s text on mining be distributed to the provincial governors, and that Schall himself should leave the capital to teach mining, gunnery, and water conservancy to the troops.

The Jesuits’ most durable appeal to official recognition in China, however, lay in their professed knowledge of the stars. The problem of calendar reform became particularly topical during the 1590s, when Ming officials debated proposals for correcting the system then in use at the imperial Directorate of Astronomy (Qintianjian) for preparing the annual calendar, an affair of state which carried great cosmological and political significance. In 1605, Ricci wrote from the Chinese capital to his superiors in Rome with a request for a Jesuit knowledgeable in compiling ephemerides, arguing that participation in calendrical reform would secure the Jesuits’ status and position in Chinese society. By the early 1610s, the Ministry of Rites, which supervised the Directorate of Astronomy, had taken notice of the Jesuits. Some were proposed as experts whose calendrical knowledge should be translated into Chinese.

While awaiting official endorsement, the Jesuits and their supporters continued to work on Chinese presentations of European science. In 1626, Li Zhizao edited the Tianxue chuhan (First collection on the Learning of Heaven), a compilation of twenty works authored by Jesuits and Chinese converts since the time of Ricci. The first ten titles, comprising a section Li categorized as dealing with li (principles), included Sambiasi’s text on the soul and Aleni’s discussions of world geography and European education. The second section of the collection, devoted to qi (concrete phenomena), consisted of works on Western hydraulics, mathematics, and astronomy, including the Tianwen lüe (Catechism on the heavens, 1615) by Manoel Diaz, notable for its brief recitation of Galileo’s recent telescopic observations – the phases of Venus, Jupiter’s four moons, Saturn’s odd appearance, and the revelation that the Milky Way was composed of many small stars.

In 1629, the Ministry of Rites proposed the formation of a new office for calendrical reform on the strength of a solar eclipse prediction by Xu Guangqi, one more accurate than either the Chinese or Muslim calculation submitted by the Directorate of Astronomy. The personnel of the new office in Beijing eventually included not only longtime proponents of the “Learning of Heaven” in China – Xu Guangqi, Li Zhizao, Li Tianjing, and Longobardo – but also newer Jesuit recruits, including Johann Schreck, Giacomo Rho, and Johann Adam Schall von Bell, all of whom had left for China in 1618 with Nicolas Trigault in expectation of such work. In a 1629 memorial to the emperor, Xu Guangqi enumerated the astronomical problems which required solution: values for precession, the tropical year and the obliquity of the ecliptic; the apparent and true motions of the sun and moon; planetary theories; and eclipse prediction.

During the early 1630s, Schreck, Rho, Schall, and their numerous Chinese colleagues in the new calendrical office produced a wide assortment of materials in Chinese pertinent to calendrical reform, ranging from essays on planetary theories, tables for calculating planetary positions, and explanations of the mathematics necessary for calculations, to ephemerides, star atlases, and descriptions of instruments. These texts, presented to the throne between 1631 and 1635, were known as the Chongzhen lishu (Writings on the calendar from the Chongzhen reign) after the reign title of the ruling emperor.

Recent scholarly work has shown the extent to which the observational and computational practices of Tycho Brahe and his associates, Christen Sørensen (Longomontanus), and Kepler were incorporated into the works composed for the calendar reform project. The technical parameters, values, and methods in the Chongzhen lishu texts which dealt with solar and lunar motion, planetary theories, and tables were generally Tychonic in origin and largely drawn from the work of Longomontanus, who provided a comprehensive treatment of Tychonian astronomy in his Astronomia Danica (1622). Jesuit presentation of astronomical instruments and observational methods was likewise colored by Tychonian influences. Xu Guangqi envisioned the construction of new astronomical instruments as one of the new calendrical office’s central tasks. Most of those discussed in the writings offered by the new calendrical office were based on instruments used by Tycho, and described in his Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (1598). Schall and Rho also relied on Kepler’s Astronomia pars optica (1604) in presenting methods and instruments for the accurate observation of eclipses and of solar and lunar diameters, and in explaining certain kinds of optical phenomena, such as the effects of atmospheric refraction on lunar eclipses.

Much has been written by modern scholars on the Jesuit failure in China to introduce the heliocentric system of the world, a breakdown in cultural transmission often assumed to be fully explained by Jesuit adherence to the Catholic Church’s decisions in 1616, which silenced Galileo and censored Copernicus’ De revolutionibus (1543) and other texts teaching the heliocentric thesis. Such European contexts for Jesuit astronomers should be considered alongside the Chinese contexts within which Jesuit astronomers sought to display their abilities. In 1612, Sabatino de Ursis prepared a lengthy report for his Jesuit superior concerning the calendar correction, explaining that the matter consisted of resolving two astronomical issues. The first was that of equinoctial precession; the second, of planetary motions, with the ultimate goal of attaining accurate eclipse predictions. More than a decade later, Schreck echoed De Ursis’ assessment of the calendar reform’s central problems in requesting assistance from the Jesuit mathematicians at the University of Ingolstadt. Schreck asked his fellow Jesuits to forward any relevant work done by Galileo, his former colleague in the Accademia dei Lincei, as well as the Hipparchus long promised by Kepler, which was to deal with the complex issues raised by eclipse phenomena. The Directorate of Astronomy was a competitive forum which required the Jesuits to test specialized knowledge and technical skills against established practitioners and a long indigenous tradition of astronomical work, and although the year 1644 brought recognition for the Jesuits as official astronomers from the new Manchu rulers of China, their position was never entirely secure. Jesuit focus on predictive accuracy over cosmological reality in this environment may have had as much to do with the demands of the Directorate’s well-defined functions as with the constraints of ecclesiastical decisions made in Rome.

The Jesuits’ scientific ambitions in China successfully weathered the dynastic change in 1644. Schall critiqued the calendar prepared by the Directorate of Astronomy and submitted a prediction for a solar eclipse, competing successfully against two rival predictions made according to Chinese and Muslim methods. Rewarded with an official appointment in 1645, Schall presided over the Directorate of Astronomy for more than two decades. Effacing the title of the previous reign from the materials which his fellow Jesuits and Xu Guangqi had translated in the last years of the Ming dynasty, Schall presented a revised version of the collection to the ruling emperor as the Xiyang xinfa lishu (Calendrical writings according to the new Western method, 1646); the calendar Schall prepared also proclaimed the use of the “new Western method.” This was a tactical error. In his collection of anti-Christian essays, Budeyi (I cannot do otherwise, 1665), Yang Guangxian warned of the danger that adopting new calendrical methods posed to dynastic stability, and emphasized the cultural importance of retaining the traditional methods of both Chinese and Muslim astronomers. Combined with accusations of missionary-sponsored plots against the government and attacks on Schall’s work at the Directorate, these charges, launched during the Oboi regency (1661–1669), resulted in Schall’s removal from office, house arrest for Schall and his fellow Jesuits in Beijing, and banishment of the other Christian missionaries in the provinces.

A few years later, however, Ferdinand Verbiest followed Schall’s example in pointing out errors in the calendars submitted by the Directorate of Astronomy. Verbiest bested his opponents in a series of competitive predictions of celestial phenomena, conducted under the attentive eye of the young Kangxi emperor, whose personal intervention permitted Verbiest to reassert Jesuit control over the agency’s work. Verbiest assembled most of the texts which Schall had already presented to the throne, a collection known as the Xinfa suanshu (Mathematical writings according to the new method), and presented a set of “perpetual” ephemerides to the throne in 1678, calculating planetary positions for the next 2000 years as a compliment to the Kangxi emperor’s reign. Verbiest also made significant changes to the instrumentation at the imperial Beijing Observatory, constructing six large bronze instruments on Tychonian models between 1669 and 1673. These reflected the state of European instrumentation for positional astronomy around mid-century, when Verbiest left for China.

After 1669, Jesuits at the capital tried to show that their scientific knowledge extended beyond their duties at the Directorate of Astronomy, to embrace all branches of European mixed mathematics: gnomonics, ballistics, surveying, mechanics, optics, catoptrics, perspective, statics, hydrostatics, hydraulics, pneumatics, music, clockworks, and meteorology. In his Astronomia Europaea (1687), Verbiest described how he and his fellow Jesuits cast new cannon for the emperor’s campaigns, surveyed for imperial waterworks, designed pulley systems for moving heavy materials, and constructed sundials, anamorphic paintings, telescopes, water-pumps, musical instruments, clocks, a thermometer, and many other mechanical devices. Over a period of several months, Verbiest visited the Kangxi emperor (r. 1662–1722) on a daily basis in order to explain Jesuit scientific texts to him in person. Imperial interest in European mathematics and astronomy extended to practice, and the emperor learned how to survey distances and to identify each star by name. Yet there were limits on Verbiest’s efforts to expand the scope of Western learning in China, and to cultivate receptive audiences beyond these bureaucratic and courtly confines. He solicited imperial patronage, for instance, in printing an edition of European – i.e., Aristotelian – philosophy; he hoped that an imperial endorsement would give European ideas renewed currency among the Chinese scholarly elite. But despite Verbiest’s claim that such knowledge was essential for truly understanding the European mathematical astronomy already in use at the Directorate of Astronomy, the Kangxi emperor rejected the Jesuit’s request.